Senate testimony: AI risks to the financial sector

In a world where AI algorithms can already analyze real-time financial information and make high-stakes trading decisions with little or no human oversight, our financial regulations are failing to keep up.

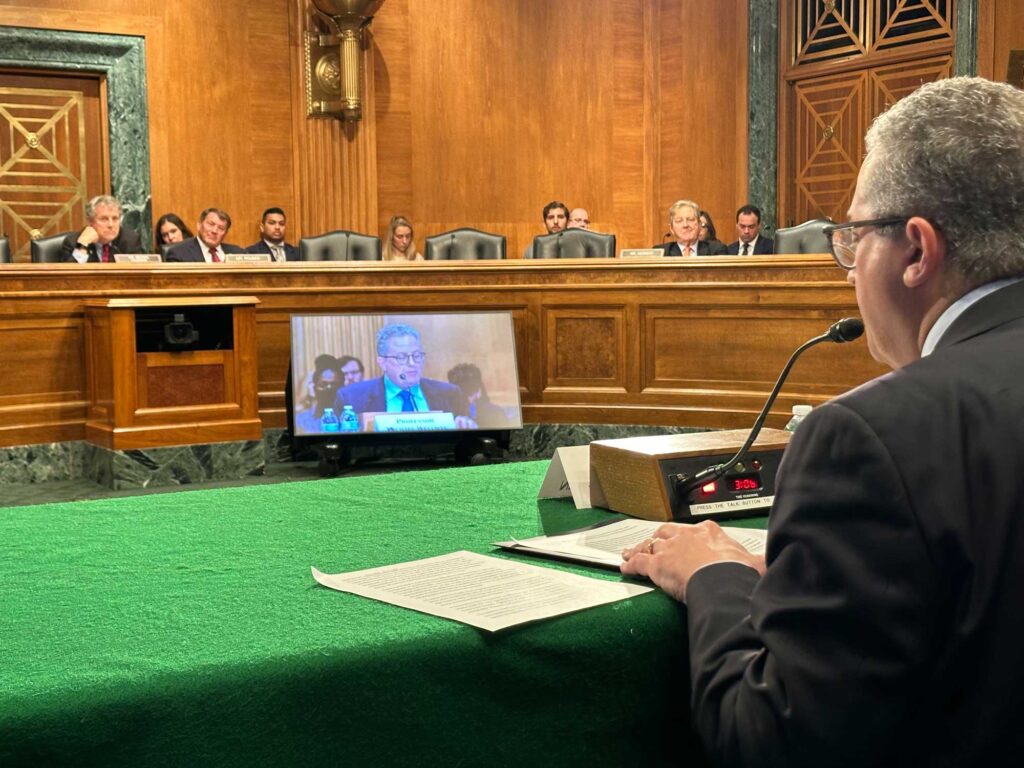

Michael Wellman, the Richard H. Orenstein Division Chair and Lynn A. Conway Collegiate Professor of Computer Science and Engineering, testified this week in front of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs to alert lawmakers to the potential dangers to security, safety and equity posed by AI’s use in financial systems.

You can watch a full recording of the hearing at the Committee website.

“Our existing laws, generally speaking, are written based on the assumption that it is people who make decisions,” Wellman said. “When AI makes the decisions, do our laws adequately ensure accountability for those putting the AI to work?”

The potential danger to the economy comes not only from bad actors hoping to use AI to manipulate markets or extract financial information. Automated algorithms that are simply designed to maximize profit could be just as concerning, according to research led by Megan Shearer, a recent Ph.D. graduate from Wellman’s group.

Their research demonstrates how a trading algorithm could learn to manipulate markets without explicit instruction to do so. This potential mismatch between a developer’s specification and an AI’s actions raises questions on how to hold AI developers accountable for the agents they release into the world.

“Much of the existing law depends on intent to manipulate, and how that would apply to an AI algorithm that learns manipulation on its own is unclear,” Wellman said.

Such a loophole could allow AI developers to avoid accountability for their AI.

“We need to find ways to define intent in the context of an AI system,” Wellman said. “Unfortunately, it’s hard to know how to improve oversight of AI given the industry’s secrecy and the difficulty predicting what might come next.

“If somebody tells you they know where AI technology will be in five years or ten years—or even next year—don’t believe them. Even gauging the exact extent and nature of an AI employed in algorithmic trading today is not possible, due to a lack of public information.”

Wellman believes that creating more public and open knowledge on what practices can create risk will help to better prepare financial systems for AI and inspire market rules and systems that remain resilient to AI’s inevitable impacts.

“Simulations of how AI behaves in test environments that resemble real financial systems can help researchers and regulators better understand an algorithm’s behavior before putting it out into the real world,” Wellman said. “We must tease apart which practices and circumstances help versus hurt—and identify market designs or regulations that promote beneficial practices and deter harmful ones.”

That open knowledge is necessary for regulators to be able to respond to AI before it poses a serious risk, which is “sometimes essential to avoiding really terrible outcomes,” according to Wellman.

AI could also exacerbate the trading advantages of parties with access to masses of information, he said. Because the firms with the most data can build the most capable AI, firms that monopolize data could obtain superiority in financial trading. Monopolizing information assets for trading has not been widely studied or discussed to date.

“Should training data be regulated as if it were akin to insider information? That’s something that lawmakers need to think through,” Wellman said. “If markets are viewed as unfair due to issues like manipulation or information advantages, it could undermine confidence in the overall system and degrade the essential process of capital formation for the economy.”

This story was originally published by the University of Michigan News office.

MENU

MENU